An Essay on Existence

© Gregorius Vatis Advena 2012, Record T 2, Engl. An essay on existence, June 2012 to September 2012, Oxford, revised 2015, literary speculations, English.

© Gregorius Vatis Advena 2012, Record T 2, Engl. An essay on existence, June 2012 to September 2012, Oxford, revised 2015, literary speculations, English.

The meaning of existence and non-existence, with its nuances and implications, is a common enquiry. Any concept will lead to the transcendent questions of origin, essence, limit and purpose.

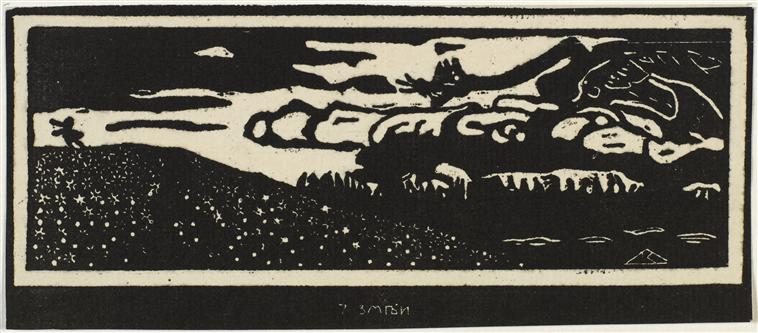

Image: Wassily Kandinsky: The Dragon, 1903, Paris, Centre Pompidou.

An Essay on Existence is a speculative work on the cause of existence in its material and intellectual totality. It studies the relation between truth and non-existence, freedom and existence, purpose and commitment. The sections alternate between strict argumentation and dialectic contemplation.

Background of rain and thunderstorm.

In the current context of both analytic and dialectic philosophy, this work is only possible as a piece of irony. Reason can only enter the forbidden territory of speculation when it is ready to laugh at itself. Though sometimes clad in sobriety, a philosophical comedy is at hand.

One of the innocent crimes of slow readers is their immersion in fiction, a dangerous sea.

It is common use for many to approach existence from existing things and to regard a thing as a thing in itself and relating to others.

I was getting a load of my smartphone down the road, bro, and I got it in my mind now. This stuff will take over, it will.

We saw that all elements identified are bound in a common bond of identity, the primitive relation among all elements.

Hey, bloke, why are you sitting in the cold here like gaga? Gosh, you’ve just rubbernecked at me like a frightened sheep!

I should not touch the question as to whether and to which extent gods exist, not even for the sake of my friend Eustace.

Earlier I told thee. Whatever exist, taketh place. Dunno, dude, it’s kinda weird, like if I think of a point, just like that, a point.

Vexation of spirit, spirits thousands of years succeeded, divine and sublime: Nothing now. Gone is the glory, perfection died in Descartes.

As I lost one or two words on the notion of primitive essence before, on freedom as an element intrinsic to existence and without cause...

It’s just that, really, I’m going away for the next few days... It’s a farm, you go there for some days and they teach you stuff and something.

| An Essay on Existence |

One of the innocent crimes of slow readers is their immersion in fiction, a dangerous sea. For a long time, I followed the steps of a certain Mr. Pip and his expectations. I am a late sailor on the main, exploring waters that everyone knows. Yet perhaps I may bring some old but not odd thoughts under the patronage of a friend, speaking as I am to a familiar circle.

Expectations! There is much to say about them, since even they who claim to expect nothing nurture in their eccentric goal an expectation. There is nothing concrete or abstract that man cannot wish too much, and whoever wishes too much is in pain. Mr Pip had a few hopes, and two of them I call great: the wish to save a man’s life and the wish to be loved. Once he takes notice of his existence in the world, he fears:

“At such a time I found out for certain, that this bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard; and that the dark wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dykes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing, was the sea; and that the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was Pip.”

1

Early in life, Pip has already one expectation: love, and his temple of love is his family’s resting place. Implicit in his first impression of the world is that feeling of loneliness in the marshes. Pip loves the impossible – his dead parents at first and at last the heartless. Because his is the love of the unattainable and because anguish makes the world so ugly, he weeps.

O how love expects! So many dreams and sorrows were told that we know, from the very beginning, what Pip will suffer:

“I had never thought of being ashamed of my hands before; but I began to consider them a very indifferent pair. Her contempt to me was so strong, that it became infectious, and I caught it.”

Before his encounter with pride and humiliation, Pip was innocent. Now he was lost – corrupted by Estella’s contempt and by his own innocence.

Estella appeared suddenly, a young girl coming across the court-yard “with keys in her hand,” aye, the keys of many sorrows. “She was very pretty, and seemed very proud.” She was the unattainable, and Pip loved her – Pip, the bundle of shivers in the middle of scattered cattle.

2

“It was a dry cold night, and the wind blew keenly, and the frost was white and hard. A man would die to-night of lying out on the marshes, I thought. And then I looked at the stars, and considered how awful it would be for a man to turn his face up to them as he froze to death, and see no help or pity in all the glittering multitude.”

The multitude of stellae in the distance was Estella! Pip knew her nature: “very proud, very pretty, very insulting.” And yet, his love could not but adore an overwhelming shine. What else was there to admire? And here we sit and wonder what has become of “the beauty of love”.

1. It is common use for many to approach existence from existing things and to regard a thing as a thing in itself and relating to others. Yet the definitions of existence, relation, thing and self are often imprecise. If for instance the self be the relation relating itself to itself, we should establish first the meaning of both relation and self. Defining self, however, is a rather difficult task. One can resort to a tautology, which defines x by saying that x is x, but that is not useful. Why? Because, if we change x for self, we would say that self is self, while self is a name that should be defined by a proper defining phrase, and not simply by saying x is x or self is self.

3

2. Yet we need to start our approach somewhere, and the concept of relation seems a good place to start. One might assume that relation is any operation involving more than one element, and an element is any object of thought conceivable. Take as an example x and y in the relation (x+y). Here, x and y are given, and it is assumed that they have their own identity, whatever this be. But the plus sign is not given in the same way, having no distinct identity. It only appears in dependence on things that have a distinct identity. This is not enough for relation to be: Relation must involve elements possessing identity.

3. Nevertheless, in arithmetic terms some operations only require one element. Something like (x : 2) requires only x as a parent element of two derived elements, for instance y and z. Whether x existed as such and created, through division, two distinct entities, thereby ceasing to exist, or whether x never existed and was only a fortuitous combination of (y+z), whereby both y and z were never part of each other but only happened to be misunderstood as one body such as x, which appears to be but is not, cannot be ascertained here.

4. Relation is the phenomenon through which an identifiable element touches another or itself. It is an extension of these parent elements. It cannot exist without the elements.

4

5. Relation is not intrinsic to any element, because an element is conceived independent of others. Relation is not a necessary condition for identity. Yet this may be different if we enquire about awareness. Does relation require awareness in order to be? Must the elements of a relation be aware of their identity and relation, and must we as observers be aware of their being and relation? Here the element is aware, there the observer is aware. Or can relation occur irrespective of any awareness? If no awareness be required, relation may be given to elements in a manner unknown to themselves and to observers.

6. Be that as it may. Once we know that more than one element is given, there will be relation. The elements may lack awareness, but with the observers it is different: If they are aware, they know, and if they know, they are aware of the elements. Because they are aware, their awareness brings the elements into a relation with each other. The relation is the awareness of what the elements have in common, and what they have in common is this: They are perceived and identified as elements. We know not how they arise, yet we are aware of their identity. The elements identified are bound in a common bond of identity. This is the primitive relation among all elements, in whatever form they may or may not exist. The elements conceivable form the class of conceivability, or class C. Following this, all elements that we identify as existent are bound to the primitive relation of existentiality. Together, they constitute the class of existentiality, or class E. Yet whether every identifiable element be able to exist, either because it exists and was not identified or because it may arise by randomness although it does not yet exist, is disputable.

5

7. What a curious conclusion arises from that reasoning: Relation does not require existence. Eustace, a poet and old friend of mine, cultivated throughout his life a most intriguing relation with Apollo Leschenorius, the converser, to whom my friend, as he claims, owes much of his poetry and some of his debts. What concerned me most in that unusual affair was the dilemma of Eustace’s creativity. Either did he converse with an actual entity, leading him through the path of art, or the entity did only exist inside my friend’s creativity. If, as he hopes, he engaged in a profound relation with an artistic divinity, he led, I must say, the most delightful life, and his relation with Apollo was just a further affair between two entities inside the class of existentiality. But, if his Apollo not exist, the scenario is not less interesting. It may be even instructive for our purpose (which is in fact my purpose, but I call it ours supposing that one of my generous readers will embrace it). Such a scenario would evidence, through the character of the relation and of the entities involved, an interaction between the class of existentiality and a supposed class of non-existentiality, i.e. existence positively relating to non-existence.

8. Having examined a particular concept of relation, let us now concentrate on the self. We would be reasonable if we assumed one thing: If the self be only itself, it must bear no divisibility such as (x : 2). Here is the reason: If x can be divided in such a way, becoming two different elements, x has never been one but only appeared to be. Now seen as an indivisible element, the self is one and what is one cannot behave as if it were two. Relation within the self would only be possible if the self were able to bear more than one entity and were thereby divisible, becoming two or more. Yet the self, which is one, is one on account of its indivisible identity.

6

9. Moreover, if the self be itself, the self is itself and nothing else. Thus, x cannot be y, and y cannot be x. The only way for x as a self to relate itself to itself is, at first, to establish a case of identity: (x=x). There can be no further definition for the self than a tautology, and because a tautology has no distinct definiens, there is no distinct definiens for the self. And because the self by means of this very tautology is itself and nothing else, the self is often defined by what it is not: The self is nothing – but itself.

10. The understanding of what belongs or belongs not to the self oftener requires more than logical reasoning. Pip may ask: Who am I? And he may answer: I am myself. But what and who is myself and how am I myself? How can I make a distinction between my indivisible self and the things surrounding it? Once these questions arise, the self becomes aware of its own existence, and this very enquiry acts as the starting point of existence: If I am asking what I am, I must necessarily exist, nay regardless of what I am, I exist.

11. If we consider the fact of existing in its human expression, there is an element in the above reasoning which does relate itself to itself. It is the self thinking about itself. The proposition “the self is the relation relating itself to itself” can be thus extended:

7

12. Firstly, through thought, the self divides itself into thoughts but keeps an indivisible identity, as it bears not the thought that it has more than one identity. The thoughts through which the self relates itself to itself do not change or destroy the primitive thought that the self is indivisible and that all thoughts must be divisible extensions from an indivisible, primitive thought, which is the intellectual core of identity.

13. Secondly, it is true that the self may exist without reasoning, as x is x with or without the awareness that x is. Yet, wherever x cannot think for itself and know what it is, it is I who assume that x is x. In assuming this, the “is” of (x is x) may mislead the observer. It states only that x is an element and that x is whatever it be. But, it states not what x exactly is. Only x itself can know what x is. I only know the manner in which I see x.

14. Thus, let us concern ourselves with a more concrete concept of being: The being of what I am and what thou art. We search not for a Holy Grail, but for the human dimension of existence, based on that particular quality of reasoning which, in myself, relates the self to itself, namely myself thinking about myself. Is the self, then, a relation relating itself to itself? In terms of human existence, the self often acts as (though: acts as ≠ is) such an intellectual operation. Because this is an act of understanding, the self of an individual is, at first, its understanding of itself.

8

15. Existence may refer to three different things. One thing is the fact of existing. If I know my existence, I am aware of the fact that I exist. Another thing is the class of existentiality, or class E. If I enquire what elements belong to existence, it is mainly to the class E that I am referring as existence. Thirdly, there is existence as a generic term for single existing things, which I will call existents or simply ee (from existing elements, while I shall use ee for singular and plural alike). Considering now our object x as an ee, the question as to whether or not existence precede essence refers to existence as the fact ot existing. The fact of existing being different from the fact of non-existing, x exists when it takes place.

16. Knowing that x exists, we may enquire what it is, and by describing what it is we give that existent a particular character: its essence. Essence characterises any ee. In terms of theoretical contemplation, ee precede essence. I cannot enquire what x is if firstly I know not that x exists. Awareness of essence requires a previous awareness of existence, or at least awareness of identity. Yet, whether essence previously require the fact of existing in absolute terms is a different question. When we become aware of an ee and ascribe essence to it, we do wonder: Does essence add to an ee something that the ee was not before? Or has essence been always intrinsically attached to ee? In the first scenario, essence was not intrinsic and was created by the observer; in the second scenario, it has always been there and was not created, but simply discovered. Be that as it may, the difference between existing and being in modern treatises arose from a shift in the usage of the verb to be, which, other than the Greek εἶναι, is used less and less intransitively. It remains true that the fact of existing is the same as the fact of being, and that if x exist, x is. Yet since the verb to be refers both to the pure fact of being and to the qualified fact of being, one tends to refer to the pure fact of being as the fact of existing or, more vaguely, existence, reserving the verb to be to the qualified fact of being, or essence.

9

17. In the case of inanimate ee, it is easier to assume that the fact of existing and essence are the same thing. We know not exactly what a stone is, yet we look at a stone and describe it. By means of similar descriptions, we become aware of the stone’s essence (quality) as its own existence (fact), and vice versa, in one phenomenon. But does human existence have an intrinsic essence? Some were tempted to describe modalities of behaviour as human nature. Many people are evil, so man would be evil by nature. Yet, what x can be is not what x is. Whether good or evil, man can be everything that it is possible to be, and man will be what man wills to be. Thus, the fact of existing presents us with choice. Intrinsic to human existence is not the quality of a choice, but the simple fact that choice is given.

18. Yet, from the fact that freedom is intrinsic to human existence follows not that freedom is the only essence of human existence. One could argue that freedom is inherent in any identified elements. Note that identified elements (ie) or identifiable elements (ie*) can be existing elements (ee) and non-existing elements (ne). If x be an ie, the identity of x is free from the identity of any other elements. Even if x be part of a relation with existing elements, the identity of x takes a particular place, and this place cannot be taken from x without destroying x. Thus, freedom is the place which x takes by means of its mere identity. The freedom of a stone is its distinct identity. The same applies to human freedom. Yet we are able to manifest freedom more ostensibly: because we act. We make use of choice. Through choice, we give existence a particular character, adding essence to it. However, any identified element can be qualified by essence, independent of existence. The white unicorn can be qualified as tame and not exist. Apollo can be deemed perfect and not exist. Therefore, essence does not require existence. Moreover, by saying that an element was identified, we mean simply that it was conceived and ascribed a particular identity, regardless of whether and according to which criterion the identity be true or not true.

10

19. We must also distinguish between two kinds of essence. Because x cannot have an identity without being free, i.e. independent of all other elements, freedom is the primitive essence of identity. This freedom we share with all elements that can be identified. Yet, because we can make use of choice, we can add a particular character to our existence, transforming primitive essence into derived essence, as this latter essence derives from the use of choice. Therefore, though existence (fact) not precede its primitive essence, existence does precede its derived essence. While freedom pertains to any kind of ee or even ie as its primitive essence, ee require a particular use of freedom in order to create their derived essence. This particular use is ability of choice. It is given to any existents such as us – capable of acting, aware of ourselves and our actions, responsible for choices, and thus differentiated from existents deprived of reason or intellect or life.

20. I was getting a load of my smartphone down the road, bro, and I got it in my mind now. This stuff will take over, it will, but I thought to myself, you know: What the hell? That whatsit isn’t quite there and we kind of become part of it. I don’t know, not my onions, just saying. But actually, man, do such programmes and what-d’you-call-it exist? That’s a good quiz indeed! People come out with things like “ugh! we’re not living in the real world anymore, it’s all run by computers, yeah, just keeping a lid on us!” We get that 24/7, you see, but I don’t know. Are we really being driven by virtual bullshit? I mean, it’s not about words or who’s ruling the roost. There may be a misunderstanding here. What does virtual mean, for heaven’s sake? Does it mean not real? Then it’s rubbish. I’m just touching my smartphone, look, you can touch your lap-top, too. The hardware is there, isn’t it? “Yeah”, they say, “but I mean the software!” But look, the hardware is holding the software, so the software takes its place inside the hardware. Get the message?

11

21. It’s just like a bloke thinking. He must have got a brain if he’s a decent guy, mustn’t he? Well, the brain will be lodging some thought inside it, too, as if it was software. What? You can’t say the thought doesn’t exist just because you can’t touch it with your mitts. So don’t flip out because of software. It does exist. It takes place inside your hardware. It’s not a big mouth like us, but it takes some language on board. Come on, bro, it’s not Godzilla! It just gets the drift of a bit of language we give it. Actually, it’s our language they catch on to, not theirs, like a mirror of words. They don’t have a will, they do what they’re told to do. They don’t think, they just decipher thoughts and show them on someone’s hardware, and that’s it basically. But exist they do, sure!

22. But how do software, programmes, Internet and what’s-its-name exist? I guess they’re sort of an extension of our mind, yeah; they make it easy for more people to keep talking and bragging about, like one guy is in China and the other guy in Miami. They don’t know each other but they talk to each other or something, whatever. But hang on a second, hang on, let me finish: What they think they’re always thinking for themselves, you see, it’s not like if their smartphone was thinking for them. I mean, some bros would rather have it this way, I know, but it’s not like that. The software, the web and what-the-hell don’t think for us, they don’t even think with us, they just show what we think, because we told them to do so. It’s just that really, it’s crazy people give a toss to that.

12

23. There’s no virtual reality, mate, there’s just reality. The Web & Co. is a platform with real people networking. What are you talking about? You mean, you’re afraid of sort of computers getting like big mouths? I don’t think they will. You’d need to cook up some of our thinking cells and get them inside a metal box. Will that work? I mean, it may work one day, but if it does, so what? If shit happens, darling, it’s because someone let it happen, and if you don’t want it to happen, stand up or shut up. People are so full of what-ifs. But folks, you’re not bots, you can stand up for yourselves. True, some goddamn bots are sort of tailing people in their loos with hidden cameras and what have you, that’s true, that’s very true. The big brother can watch you stroking here and there. But take it easy, my friend! Is it really so surprising? Since time began, any old top brass did whatever they could to know what their folks were doing. Even the Romans would have gone for it if they had the technology. Of course we have something to hide, everybody has. But they just know, dear, they know what you did last summer. If that’s an issue for you, join the right party and have a go at them. But wait! We’re not talking about surveillance. We’re talking about virtual reality and reality. So keep in mind that surveillance is not virtual reality, it’s just reality.

13

24. Now listen: A bot keeping an eye on you is not actually a guy like you. It’s still a bot, so he who keeps an eye on you is not the damn bot, it’s the top brass. But that’s not the issue, the issue is this one here: If some bots become like us, and just like us, what to do then? That’s the question. But you know what? I’m just cool, really. Why have cold feet about it? You see, people can kill and do all sorts, but you don’t fear people just because they’re there. If bots became exactly like humans, then why fear? As if they wouldn’t be afraid of us, too! Of course they would, ’cause if they became like us they’d have some kind of aura or funny feelings too. Just figure out in your nut, bro, a bot falling in love with you!

25. What? You mean, they won’t feel, they’ll just have the intelligence? Come on, man... then they’ll be harmless, they’ll be like a calculator. I tell you why: It’s feelings that make intelligence dangerous, not intelligence itself. Intelligence is cold, it’s like maths. It still may have a will of its own, I know, I know. But just think: If there’s no feeling, there’s no pleasure. If there’s no pleasure, there’s no purpose for the will to get funny and sort of ambitious, is there? You mean, a sense of duty? No, dear, there’s no duty without emotion, ’cause people’s duties are the duties they choose to obey, and if they really don’t want to obey they won’t, no matter the price they’ll pay for that. There’s always a degree of choice and heart with any old duty. So have a think about that. If you prove me wrong, you get a pint for free.

14

26. What’s wrong with you? Are you saying that if bots were like us they’d need to be controlled in some way? Just dig it, bro, dig it. If you turn robots into humans, into people like us who think and sort of suffer like us, if you do that, bro, the first thing these new people should do is to get rid of you, of us all! They must! I don’t mean they must do for you, it’s not that. But if they’re equal to us, then, my man, they’ll have their rights too. Dignity, dig it, dignity! Now then, what sort of life would they have if you create them to be and feel just like us but wanna have them as slaves? That won’t be right! They’ll have to stand up for their rights, yeah, and get rid of you to live a decent life, free, thinking and feeling for themselves. Otherwise, what the hell are you doing? You don’t want to turn things into real people to have them behaving like things! But anyway, if it’s just people you need, just knock up your chick. If you create something human, you can’t create a purpose for it, ’cause people are free to create their own purpose. Seeing daylight now?

27. I know, I can hear them saying:

“Yeah yeah, that’s true, that’s all true, but even if bots don’t become real people, their intelligence may become more sophisticated. They’ll learn our language and speak like us. You may be talking to someone on the street thinking the guy is real, but the guy’s just a bot, you know, it’s just weird, it’s creepy.”

15

You know what? That’s right, actually. Life and language will become more complex and more confusing. But language is not only about who’s talking to you, but even more about what’s being said. You don’t need to be a real guy to take some language on board. Books have been telling you things for ages and you didn’t mind. Just tell me one thing: You buy the book because of the words or because of something else, like the way it looks? It’s because of the words, or pics, whatever. It’s because of the content, anyway, that you get hold of it. So you’ll sort of size the book up from the content, not from the colour of the cover. True or false?

“True!”

28. So it’s the message that matters, not the means. The book is just the means. Now what about the talking bot, is that a real person?

“No.”

So it’s a thing?

“Yes.”

But if it’s a thing, it’s like a book then, isn’t it?

“I guess it is.”

Well, but then you’ll judge it not just from the creepy look of it, but from what that thing is telling you, whether it’s true or bullshit, isn’t it?

“That’s true.”

16

29. Then there’s nothing to worry about things talking like people but still being things.

“No, but it’s the control they can have on you, that’s the danger!”

Which control, bro? They have no true will. Their will is the will of whoever set them up.

“Yeah, but then they make it easier for us to be controlled.”

I told you before, bloke, it’s not the bot’s fault. The bot doesn’t know what it’s doing and what’s going on. You need to sort that out with the guys who set up the bots.

| An Essay on Existence |

30. We saw that all elements identified are bound in a common bond of identity, the primitive relation among all elements. The elements conceivable form the class of conceivability, or class C. Within the class C, all elements that we identify as existent are bound to the primitive relation of existentiality. Together, they constitute the class of existentiality, or class E. Yet whether every identifiable element be able to exist, either because it exists and was not identified or because it may arise by randomness although it does not yet exist, is disputable, as we observed earlier. Such a class of all that is able to exist, i.e. the class of existentiability, would be the absolute class, encompassing existence (class E) and the supposed non-existence (class N). Note that existentiality and existentiability are two different names. The class of existentiability, if it be given, cannot be encompassed by any other. If another class encompassed the class of existentiability, then this would be the absolute class, and so on.

17

31. Many were tempted to enquire the cause of existence, since the only thing we know is that whatever exist is simply there. In other words: The class E is given. Whether it have a particular cause or, while being simply given, be also free of cause and origin, is a question worthy of enquiry, yet difficult to answer.

32. It was noted that, with the name existence, we may refer to three different things. One thing is the fact of existing. Another thing is the class of existentiality, or class E. Thirdly, existence is a generic term for single existing things, or existents (ee). It was also seen that the difference between the notions of existing and being arose from a shift in the usage of the verb to be, which, other than the Greek εἶναι, is used less and less intransitively. The fact of existing is the same as the fact of being. The verb “to be” refers both to the pure fact of being and to the qualified fact of being, yet one tends to refer to the pure fact of being as the fact of existing or, more vaguely, existence, reserving the verb “to be” to the qualified fact of being, called [derived] essence. While referring to being, we need always to clarify whether we are referring to pure being (primitive essence) or qualified being (derived essence). In the following argumentation, I will refer to being mostly as the pure fact of being.

18

33. The idea according to which existence arises from non-existence has always been a source of disquiet. Simple images appear to suggest such a concept: Light arises where there was no light. Life on earth arose from what was not alive. Should we say that existence arises from non-existence, as if, by natural means, a principle originated from its opposite, i.e. life from death, light from darkness, being from nothingness? Great is the temptation. But are these images really examples of the same phenomenon? Light arises, in fact, after darkness. Arises light also from darkness? Life arose, if empirical observation be of value, both after and indeed from chemical elements deprived of life. But were these elements really the opposite of life, or not rather ingredients which, put together, gave birth to life? Whatever these elements be, if we say that life arises from given elements, we cannot say that life comes from nothing, so that life arising from what is not alive is not an example of existence arising from non-existence, of being coming from nothingness. It is, rather, an example of existence suffering change and continuing to exist. The same applies to darkness: Is it the opposite or, in some way, an ingredient of light? And, if darkness be or contain an ingredient of light, can we still say that darkness exists not, that light comes from nothing?

19

34. A scent of Parmenides, the poet, pervades my thought: What is cannot not be. What is cannot not have been. Accordingly, neither does existence come from non-existence (in other words, class E would not arise from class N, nor ee from ne), nor does existence arise at all. Existence simply exists. It has no origin in time. Whatever exist has always existed and will always exist. And yet, by agreeing with Parmenides we change a source of disquiet for another one; for, while it displeases reason to believe that what exists can arise from what exists not, it displeases our time-orientated instincts to believe that what exists did not arise from anything, but has always existed and will always exist.

35. Does the class E have a beginning? Immersed in the perception of time, we may not have the means to approach this class in its bareness. Such a class is necessarily free from non-existence. If it be true that what is cannot not be, existence (class E) is not subject to beginning and ending. It is free from any condition whereby is exists now but not before, or not later. Thus, if the cause of existence be a sort of beginning, as many claim, existence cannot have a cause, since it has no beginning. On the other hand, if it have a beginning and the beginning be the cause, it has no absolute freedom, since it is subject to a beginning.

20

36. If the class E have no beginning and no end, it can neither arise nor cease, but only change. If therefore, as my friend Eustace believes, there be a powerful Apollo Leschenorius, who through his power orders and interferes with all visible things, this Apollo, together with Zeus and Poseidon, existing as much as any other thing existing, neither created anything nor arose himself from nothing. If Apollo exist, Apollo simply exists with all things, and all things exist not from Apollo, as if the god had created them from nothing, but with Apollo. If Parmenides be right, things exist with each other, transforming, yet not creating each other.

37. This requires a reflection on the class of existentiability. Some might assume that anything is existentiable, either because it exists or because it may arise by randomness. But, of course, if it be true that what is cannot not be, then nothing can simply arise by randomness, as if randomness could create ee from ne. Randomness can, at the most, transform a given set of ingredients into an expression of existence which appeared not to be there before and appears to be something new. This has one or two implications for our understanding of non-existence. If it be true that what is cannot not be, then the opposite is also true: What is not cannot be. It cannot arise and become. Furthermore, what is not cannot have been, and what is not cannot be yet to be. Thus, what exists not is not able to exist.

21

38. What does this reveal about the class of existentiability? If we assumed it as the absolute class, the class of all that exists and all that exists not, since what exists not yet might still come into existence, a contradiction would be at hand: What exists not can come into existence, said we before, and what is not cannot be yet to be, say we now. This argument is reduced to absurdity. How to amend it, which premise to withdraw?

39. Let us begin with the first premise: If whatever not exist may come into existence, say we not that non-existence may originate existence? We do. But, if non-existence originate existence, then existence loses its absolute freedom, it becomes bound to a causal agent; nay, it requires a cause in order to make it arise. And yet, if we try to discuss the cause of existence, we shall need to enquire, first of all, whether the cause of existence exist or not exist itself. If the cause of existence exist, then existence is not caused, it is only continued and transformed. Why, cause and effect were the same thing otherwise. But, if the cause of existence not exist, is that a cause? It is not. Thus, neither existence nor non-existence can cause existence. Even if we assumed that non-existence is able to cause non-existence, we would imply even then a degree of existence in this phenomenon, because a causal agent would need to act, and how could it act and not exist? Under these premises, reason is barely satisfied with the assumption that what exists not can come into existence. Let us, therefore, withdraw this premise and keep only the other one: What is not cannot be yet to be.

22

40. We do not know exactly what exists and what exists not. It is therefore necessary to acknowledge a difference between true non-existence and apparent non-existence. While true non-existence is not able to exist, apparent non-existence is well able to exist, because, being only apparent, it does belong to existence and, transformed by randomness, it may yet appear in the form in which we conceive it to be or not to be. In other words: The ingredients of what appears not to exist may exist and, at any point, they may form an expression of existence which we thought would not exist.

41. But we must be careful and amend one more thing: The class of existentiability can no longer be the class of simply all, i.e. of what exists and of what exists not. It is only the class of what exists and of what appears not to exist but exists. What truly exists not cannot be part of existentiability. It is an independent class: the class N. And yet, what truly exists not can still be conceived, and the class of what truly exists (E) and of what truly exists not (N), is the class of identifiability, or conceivability: the class C. In fact, anything is conceivable. Yet this fine distinction between the class of existentiability, or what remains of it, and the class C does not enable us practically to distinguish true non-existence from apparent non-existence, because we know not the full expression of the class E and the class N. The class of existentiability, therefore, appears not to be given as such. Rather, it arises when the unknowing mind creates an intersection between the class E and the class N. This intersection is arbitrary and represents the inability of thought to recognise with certainty what belongs to the class E and to the class N. Although we know that things may truly not exist, we know not which things these are, and, thus, we cannot refute the assumption that anything may exist and that, in pragmatic terms, anything is likely to exist. Conversely, because we do not know what exists not, knowing only what appears not to exist, we are not in a position to make any statement about what truly exists not.

23

42. Existents (ee) can be transformed, and anything that can transform existents is a power. A power is sometimes endowed with will, as the complex power of the human mind. But often, power is not endowed with intelligence or will, as the simple or primitive power seen in the mechanics of matter. This simple power may transform simple parts of existence. Note that, here, I am referring to existence as the complete set of all material elements, or the set M (matter), adding a fourth meaning to the name existence. The set M is encompassed by the class E. By saying simple parts, we are referring to the simplest parts to which matter can be reduced, i.e. matter in its point of irreductibility. Now, simple powers may lead simple parts to behave in a regular pattern, and this pattern may serve as a source of scientific knowledge. Yet other than existence (class E and set M as part of it), which cannot not have been, a particular transformation of existence, simple or complex, must have a beginning. But, because a transforming power of any sort exists and therefore existed before the transformation, the beginning of transformation occurs by chance, since the transforming power has no will and therefore no intention to begin any transformation. Randomness is the means through which a simple power manifests itself by starting transformation. Any simple power may initiate transformation at any time. By chance, it may alter the course of an electron in a way we would not expect, and what would follow we know not.

24

43. Simple powers take part in existence (set M) and manifest themselves in existence, with existence, through existence. Such powers order existing elements (ee) in a way that, though nothing be created, new expressions of existence may arise by the fortuitous combination of ingredients. By chance, and through transformation, a simple power may give rise to derived power, endowed with differentiated qualities. Bertrand Russell may have had a low opinion of speculations, and probably for the right reason. But, where the man of the 20th century sees only the unfruitfulness of metaphysics, we should try to discuss the relevance of possibilities; this little note may be important here, where we begin to follow a highly speculative path, not knowing exactly the realities that our words describe, looking for the probable, to use an expression from Timaeus. It is evident that, while referring to power, we are not dealing with an element of natural sciences. Scientific verification belongs to a later stage and to another enquiry. But, if there be no power of randomness to transform existence (set M), what transforms it then? I shall simply assume, at first, that there is, in some way, a fortuitous power able to transform existence. I shall also assume that, as a logical matter, if a power belong to the class E, and if a power may transform things belonging to the class E, a power may become itself an object of transformation and be changed from a simple into a complex power.

25

44. Another question arises when we try to discuss the character of a power, which is here a simple, primitive power: Is simple power an entity which takes place in physical reality, even if in an extremely quintessential form, or mean we, by saying power, simply the free space which randomness leaves for existence to transform itself fortuitously? We shall see. If power be only the free space which randomness leaves, we must assume that, when an electron makes free use of such a space suddenly to alter its course in a fully unpredicted way, then the electron itself would be the source of a beginning of transformation and therefore nothing else than power according to our definition. But since we know that the electron had been following its route for a long time in the way expected, an unpredicted, unprecedented and unexplained change of course would appear less plausible than the possibility that the sudden change of course manifests, not the electron itself, in a display of what would be a degree of choice and will, but a power simpler than the electron which, being unpredictable and unexplainable in its very nature, forced the electron to alter its route.

26

45. One would almost think that, in this case, the existence of our physical reality may be altered and transformed into something completely different, unexpected and unprecedented, and this in a single moment. Such freedom must be granted to the randomness of simple powers. And yet, through the very manifestation of simple powers, existing elements can be transformed into more or less resistant systems, and such could be the atomic system where the electron from above continues to display its beauties and oddities. In such systems, the interaction of elements may achieve a level of co-operation such as to resist, to some extent, the arbitrary incursions of any simple power, which resistance therefore would have transformed matter into something complex, into a system indeed, relatively immune to simple powers, so that this system, once formed, could no longer be totally dissolved or transformed against its own mechanics, or at least not easily transformed. A simple power is not of such kind that it might be able suddenly to make a dog or a cow appear out of primitive ingredients. We should rather assume that, fortuitously, small transformations take place, and that simple derived elements, fortuitously combined, amount to more and more complex compounds. Complexity, on its part, may form concrete sets of elements, and, again, sets of elements may develop their own dynamics and become programmes or self-programmed and self-programming systems, i.e. autonomous compounds functioning according to regular patterns, relatively resistant to external interference. Such systems are not able to destroy or surpass a simple power in its randomness, but through their relative immunity they may become themselves complex powers, i.e. powers derived from simple powers and able to begin more resistant, complex transformations, such as the atomic system, which may give rise to a micro-cosmos, and this to a micro-universe, and this to a macro-cosmos, and this to a macro-universe, and this to further complexity and so on. Together, all these universes will amount to the set M.

27

46. Am I stating that the simple gives rise to the complex? If we consider an electron and a planet, we do not tend to think that the planet developped the electron, but that the electron developped the planet, and we think not that the planet is part of the electron, but that the electron is part of the planet. Thus, it is the electron that institutes and forms the planet and not the planet that institutes the electron, so that the planet derives from the electron. Because a compound is reducible to simple parts, simple parts may form a compound. But a simple part is so simple that it is no longer reducible to anything else, and therefore nothing else can form such a simple part, this simple part being matter in its point of irreductibility. This would mean that the complex cannot give rise to the simple.

47. What happens, however, if the planet disintegrate? Will it not give rise to electrons? In fact, it will not, because giving rise would imply that the electrons were not there before the planet was formed, while in fact the electrons are anterior to the planet. Yet the planet was not there before the electrons and their atoms formed it, so that we may say that the electrons indeed gave rise to the planet. If it be true that the simple gives rise to the complex, living elements must have arisen from non-living elements, which are simpler than living elements. Intelligent elements must have come from non-intelligent elements, which are simpler than intelligent elements. Finally, complex powers, which may be endowed with life, intelligence or reason, must derive from simple powers, which lack life, intelligence and reason. But simple powers could not derive from complex powers.

28

48. That reminds me, of course, of my poor friend Eustace, the poet, and of his relation with Apollo, the converser. It is an established fact that certain matters of speculation should not concern a serious spirit, especially the man who is waiting for an academic favour: He is in greater need of measuring his words. But, as we are under close friends here, I may speak, as it were, entre nous, and I will certainly take my poet’s concerns into consideration, both for the love of my friends and for the love of truth. Now the poet’s concern, that it may be known, is the following: Where is Apollo in all that reasoning? Is it possible, asks my friend, that such a god exists? Judging from our reflection on power hitherto, it is possible to include god-like entities into the notion of power. My friend, however, will need to make one or two concessions on his understanding of the divine.

49. Let me please explain what I mean: If it be true that the simple gives rise to the complex, that therefore simple power can give rise to complex power, and that, if we apply this principle, non-intelligence gives rise to intelligence, since non-intelligence is simpler than intelligence – if all this be true, simple powers may combine simple parts into an expression of existence which, with some help of randomness, may amount to a complex power endowed with intelligence. Once intelligence is formed, primitive intelligence, such as the simple ability of computation, may be transformed into more complex forms of intelligence so that, eventually, will and sensibility may arise. Such a complex intelligence, being also a complex power, would be able to start transformations by its own will. Do my words sound too speculative? I am sure they do. And yet, we cannot say that intelligence cannot arise, because we exist and we possess intelligence. And we cannot say that all intelligence must have always existed, because we know that humankind has not always existed, although humankind possesses intelligence. Thus, we must conclude that our intelligent existence is derived from a non-intelligent expression of existence.

29

50. But, because we only know intelligence in the particular frame of our own existence, we cannot say whether any form of intelligence exist outside this frame known to us. We may assume as probable, however, that simple powers, being able to transform existence (ee) into more expressions than we know, may well be able to form intelligence, will and sensibility outside our animal frame. By chance, they may combine unintelligent ingredients of intelligence and thereby give rise to an independent will, endowed with transforming power, or to compounds which may develop in themselves an independent will. Such a will, being also power and, by means of its complex intelligence, aware of its own identity and freedom, may begin transformations according to a particular plan. This plan may be devised in such a way as to resist the randomness of simple powers as much as possible. A cosmos may arise, in which this complex power will make use of its freedom by performing its chosen plan. However, because the complex power will be endowed with intelligence, will and sensibility, its sterile freedom is a source of anguish. The complex power is therefore condemned, by its own existential condition, to conceive a transforming plan, which will give a purpose to the existence of this – shall we say: divine? – element. In the apparent nothingness of darkness, this power gathers the scattered ingredients of light and lets there be light.

30

51. The first concession my friend Eustace should make here begins with the origin of intelligence. If intelligent existence derive from non-intelligent existence, a complex power of divine dimension could not form intelligence from its own intelligence, as if it could create, out of dust, a dog, a cow and a man endowed with reason. It would rather start smaller transformations that eventually would amount to life, intelligence and reason.

52. Whether such a complex power be closer to the idea of Zeus and Poseidon, as my friend hopes, or closer to the nóos of the Stoic masters, I know not. What I know is that a complex power of such kind, even if it be able to conceive a plan for its particular cosmos, transforming this cosmos into a system highly resistant to the randomness of simple powers and fulfilling therein its existential plan, this complex power, as I said, is not all-mighty in such a way that it could surpass simple powers and simply destroy randomness. It may well become immune to randomness and behave inside its universe as the mightiest element, so that, in pragmatic terms, it would be all-mighty. But this powerful element would not be all-mighty in absolute terms, and this is the second concession that my friend, the poet Eustace, should make.

53. My poetic fellow, being so attached to Apollo the converser, may rather suppose that his Zeus is as old as existence (class E) itself, nay even anterior to existence. If it be so, Zeus would have caused existence, but as he himself must exist, he would not have caused, but only continued, existence. But, at least, Zeus could be existence in its highest expression, the only source of all transformations, simple and complex. Then Zeus would be a complex power creating simple power. And yet, it is the simple that gives rise to the complex and not the complex that gives rise to the simple, because the complex could be disintegrated into the simple, but the simple could not be disintegrated into the complex. Thus, neither is Zeus a creator of existence nor does his complex power give rise to simple powers.

31

54. Returning now to powers as such, we assumed before that power is anything that is able to transform existence, and that transformations take place randomly, at first by simple powers, i.e. powers devoid of life, intelligence and reason, free from any form of complexity. Please remember: We discussed also non-existence as much as to conclude that what exists not, cannot have existed or be yet to exist. We saw that, although some things may truly not exist, we know not which things these are. And yet, putting these statements together with our reflections on power, we should ask again whether it be possible that a thing truly not exist and even must not exist. Non-existence does not take place, because it exists not. But, if it be necessarily impossible that a certain thing exist, the place which this thing would have taken must be made free from any form of existence, so that nothingness would occur in its place. In this case, because nothingness would occur, nothingness would exist and therefore belong to the class E. Yet, is it possible that nothingness manifest itself by simply being there and therefore existing? This is a problem. Nothingness either exists or exists not. If it not exist, existence takes place everywhere and everywhere is filled with existence. And yet, because in this case nothingness exists not, there would be one thing that exists not and makes existence in its totality incomplete. Hence, we would have to assume that nothingness exists. Yet, if nothingness exist, it must occur in such a place where not even a simple power could exist or enter. And, because simple powers manifest themselves by randomness, the place of nothingness would be a place where not even randomness can exist. But in order for neither randomness nor simple powers to exist, there must be a thing preventing them from existing. And yet, because this thing would necessarily exist, this thing would be necessarily the end of nothingness and probably a power itself. In the face of such a problem, we should conclude that, where randomness may take place, there is no place for nothingness and non-existence, because randomness can reveal existence where it appeared not to be; and, even where randomness may not take place, there is no place for nothingness and non-existence either, because only existence could resist randomness in such a way that randomness might not take place.

32

55. One could think of a further problem, regarding the simple. If the complex derive from the simple, could not one say that existence must derive from non-existence, which is simpler than existence? This would be a fallacy, because what exists not, can be neither simple nor complex. But if, as some suggest, a being can be perfect without existing, a being can be simple without existing, too. If this be true, and if the complex derive from the simple, existence would necessarily derive from non-existence, since existence is complex and non-existence is simple. Does this make sense? A being can be conceived as perfect and not exist and a being can be conceived as simple and not exist, because a being can simply be conceived. And yet, non-existence is not a being and therefore cannot be conceived as a being and cannot be conceived with the attributes that only an identified element could have, whether it exist or not exist. Thus, non-existence (fact) cannot be simple.

56. If a being can be perfect without existing, the possibility of non-existence is assumed as obvious. Yet, is it so obvious that non-existence may take place? It is not: When we say that a being exists not, we say that the idea of the same being exists. Should we therefore distinguish between ideal existence and real existence? We may. But then, we would need to define the border between idea and reality. And yet, we know not whether idea and reality be totally different (or even opposed), or whether they belong to the same truth of existence but in different expressions. I may put it in a way that will displease one or two but is worth mentioning, only entre nous: Whether in thought or in concrete matter, ideas take place somewhere, and whatever take place exists. But how do ideas take place? Either exist ideas as pure speculation of mind, or ideas exist as simple parts, a mass of such subtleness as we would not associate with concrete reality, but indeed as matter, reduced to a simplicity greater than the simplicity we know in matter so far. And yet, if ideas be simple parts, they may be simple powers as well if we consider the images they can evoke. Because powers transform existence and human thought exists and ideas transform human thoughts by simply occurring, ideas can count as powers. We are dealing with a set of existing elements that does not belong to the set M, which comprises the concrete existence of matter. Rather, we are dealing with abstract elements of matter which would amout to the set of abstract existing elements, or set A, so that the class E comprises, so far, the set M and the set A, encompassing concret and abstract matter (intellect).

33

57. But what say we, by stating that ideas may be speculation of mind? Either ideas exist or ideas exist not. If they not exist, they cannot occur in mind. Conversely, if they occur in mind, they do exist, as they are able to take place, and whatever take place exists. And, if ideas exist and existence cannot be caused, ideas exist before they occur in thought. Otherwise, thought would be the cause of ideas, while in truth neither thought nor ideas can have a cause if they exist. They simply interact. They transform each other as mutual powers and take place in each other.

58. By thought, I mean not a particular idea, but our general ability of thinking, which as a power belongs to the set A. Now, because thought occurs in mind, thought takes place and exists. Where does thought take place? We say that there is thought, thus thought is there. But where is there? Do an idea and a stone occur in different places, as if an idea and a stone were two different existences requiring different spaces to occur? It may be. But, if an idea and a stone differ, in what way differ they? Should we say that the stone exists more than the idea? There are no degrees of half-existence. All existing things are equal in existence, and the place which existence takes is existence itself. We must not say that an idea and a stone are two different natures of existence for which there must be two different places. An idea and a stone are simply existing things, built from the same simple parts and transformed by different powers into different elements – in the same place. The elements of set M and set A, if they truly exist, must differ in their expression but not in their nature, since they interact and affect each other.

34

59. If ideas be only speculations of thought and if a stone exist “more” than an idea, as many claim, we still must agree that existence (ee) can be transformed. But, even here, because existence can be transformed, a simple power may start transformations which, fortuitously, may lead to a concretisation of the idea, so that the idea, then, would exist “more” than it existed before. Through transformation, an ee can migrate from the set A to the set M, as if A and M were quintessential states of matter. Whether or not we agree on the existence of ideas, we may always become aware of “real” things that confirm or at least correspond to an idea deemed impossible at first. Existence (set A) bears in itself all ideas, as well as the power randomly to concretise any idea. Yet no ee from the set A can create an idea which did not exist before. Elements from the set A cannot be created or caused, but only grasped by and combined with each other. Ideas, therefore, have always existed, and here we face the problem that the whole class of conceivability (class C) would then exist as an object of the set A, which should be regarded rather as a class A. Apparently, anything conceivable not only exists but already existed before being conceived, or rather identified, grasped by the intellect. It seems indeed that any idea can bear existence. Yet we should be careful with the idea of non-existence. If non-existence existed, it would cease to be non-existence. Existence cannot bear the concretisation of non-existence. But since the idea of non-existence exists and any idea may be concretised, the possibility of concretising the idea of non-existence shows that what we call non-existence cannot be totally opposed to existence, but is rather a different kind of existence. Because existence can bear all ideas, nothing can be prevented from existing. But if there be a relation between existence and truth, so that what exists is true and the opposite not true, and if all ideas bear existence, are they all also true? If all are true, what is to be called untrue and how can anything be untrue? If truth be the knowledge of the identity of things as they are, ignorance is the lack of such knowledge. It may be the case, however, that the object of truth as knowledge is not the question as to whether things exist, since apparently everything exists, but rather the question of how things exist. An untruth is therefore not a statement about an element that exists not, but rather that does not exist in the way stated.

35

60. Since truth considers not whether but how things are, we should consider attributes more carefully. Attributes belong to the category of abstractions within the class A, and we should call abstractions such ideas whose concretisation is not bound to take any form in particular. It is indeed so because abstractions take place, at first, in thought and because it is thought that decides where and how the concretisation of abstractions takes place. Consequently, the perception of abstractions differs from individual to individual. When we see a stone, we are not likely to differ on whether or not the stone be there, or at least that we believe to see a stone. But, when we ask whether or not the stone be beautiful, opinions will differ, every observer judging according as he or she may conceive something beautiful to be and to express itself. Attibutes do not need concretisation. Perfection may be no explicit attribute of any ee in the set M, and yet this does not prevent the set or class A (which belongs to the class E) from containing the idea and the possibility of concretisation for this or any other atribute. Also concepts belong to the class of abstractions. Other than attributes, which explicitly refer to different elements (as beautiful, in our example, refers to a stone), concepts refer to themselves. Love is a concept. And yet, because concepts are still abstractions, opinions will differ as to the definition of concepts as much as they do with regard to attributes. If we were to say that love is beautiful, an abstract concept and an abstract attribute would share in the same sentence and would lack an objective definition.

36

61. I am bound to include a parenthesis at this point, for the sake of my friend. Is it not amusing that, by coincidence, we should stumble on “the beauty of love” again? We must agree that, in this day and age, concepts have a sad lot, for philosophy will not greatly concern itself with “the beauty of love”. Why, what is beauty and what is love? The uncertainty of concepts is a vexation for analytic philosophy. “The beauty of love”, says the philosopher, is a frivolity only worth a boisterous poet. Yet, for a similar reason, the poet of our age does not wish himself to be concerned with “the beauty of love”. Why, concepts require definitions and definitions are not the task of poetry. I must say, Eustace would feel quite ashamed of writing about “the beauty of love”. As a poet, claims he, I am a man of metaphors. He will suggest a feeling rather than define a concept. Thus, also the poet will refuse to treat “the beauty of love” and will leave it to philosophy. Or, should they both strive for a dialogue? They could, but my friend’s attempt to address an illustrious professor failed. Unfortunately, the paid erudite was in a bad mood when my friend called in. Relegated as it is from all sides, “the beauty of love” has a sad lot to bear indeed, and as I will not venture myself to define it, let everybody judge “the beauty of love” as he wishes.

37

62. Be that as it may, one is tempted to ask, again, how abstractions exist. Whatever exist, say we, takes place. There is it and it is there. Yet, if abstractions take place and be there, what means it to be there and where is there? I gladly repeat myself: Is the stone there in the same way that “the beauty of love” is there? It depends on what the observer understands as space, because the word “there” refers to some place in space. Yet, before we discuss what may be worth being called space, allowing existence to exist where there be space and not allowing it otherwise, let us ask at first how space itself exists. Why, if space be something other than existence and yet an element required for existence to take place, then we must say that space exists not and yet is there in some way, because a necessary condition for something existing must exist itself. And yet, existence does not agree with non-existence as if a thing could exist, but not be there or be there but not exist. Thus, if space be a necessary condition for existence, space and existence must be the same thing. And, if this be true, we cannot speak of any hierarchy of space which would accredit the space taken by a stone with being more legitimate than the space taken by “the beauty of love”, or the space taken by the number 237. Once a concept arises, there is not such a thing as there being no space in existence for it. It exists. It had always existed and simply manifested itself in thought.

38

63. Let us dwell upon this last proposition for a second, or rather two. Saying that concepts have always existed, mean we to say that ideas are anterior to their occurrence in mind? This appears to disagree with the material perception of things and thoughts. Take “the white unicorn” as an example. “The white unicorn” is in no way an abstraction, neither as an attribute nor even as a concept because its concretisation must take quite a particular form. “The white unicorn” is a concrete entity. And yet, because we have no proper account of its concretisation, “the white unicorn” is a missing entity. Now we tend to think that, if an idea only occur in thought (such as the idea of a missing entity), then it takes no place, or at least no place of its own, but it is placed “inside” thought. We think that, if an idea not occur independently, i.e. “outside” thought, then it takes no real place. But is that true? Since existence itself is space and existence is real, ideas exist and take place in space and are real. We should not approach existence with geographical pretensions. Is there such a thing as “inside” and “outside” thought? If existence and space be the same thing, there is no near and far and within and without limiting existence, but whatever exist exists everywhere. It may be perceived in a particular place only, and yet it exists everywhere. How else? If existence were not allowed to exist in a particular place, there must be something preventing existence from existing, but such a preventing element would need to exist itself. Consequently, existence cannot be prevented from taking place. Existence must take place everywhere. The idea of a missing entity occurs in a particular place because it may occur everywhere and will occur randomly at particular places, which an observer may regard as near and far and within and without, but which are the same place inasmuch as everywhere is the same place in existence. Therefore, “the white unicorn” exists in thought as much as it exists and may occur everywhere. It may occur in thought. And it may occur in what we call matter if a fortuitous power start transformations which will lead to the concretisation of the idea.

39

64. Abstractions exist. Existence (class E) knows a place for them and their attributes and concepts. Yet, follows from the distinction between abstract existence (class A) and concrete existence (set M) a duality in existence? I spoke of existence “in thought” and existence “in matter” in the above paragraph. This is less accurate. Existence may be divided into modalities in order better to please observation and reasoning, and yet existence cannot be but one phenomenon and not two or three, as if existence could be added to or subtracted from existence, as if “thought” and “matter” were two distinct spaces of existence never touching each other, nay excluding each other. If existence be one phenomenon, all manifestations of this phenomenon must be reducible to the same principle, so that, without any doubt, what we call “thought” must be a modality of matter, however quintessential, and conversely, what we call “matter” must be a modality of thought. In existence, the concrete and the abstract cannot but be the same thing. And yet, a fear of insanity pervades my mind the very instant I write this. Have we considered the implications and the amount of problems and paradoxes arising from such a proposition? Why, if abstractions such as “the beauty of love” and the number 237 be a sort of matter, and if it be true what we read above about powers, then nothing could prevent a fortuitous power to start transformations, leading to what would be the material concretisation of the most abstract attributes and concepts. One day, we may stumble on two little dwarfs in the New Forest waving at us and crying: “Hi, guys, I am the beauty of love, yeah, and here’s my younger sister, number 237. Say hello to the guys, 237! What d’you mean, dear? What are you talking about? No, it’s not as if the beauty of love was just my name and I was something else, but I am indeed the beauty of love as such, it’s my very identity. And 237 is not just the label of my sister here, no, she’s nothing but the number 237 itself, that’s all she’s about!”

40

65. That would be quite an intriguing scenario. To meet personally the concretisation of a number and a concept may be worth one or two walks into the woods. It would surprise many who believe that “the beauty of love” and the number 237 only exist as products of our faculties of sensibility and computation respectively. And yet, I do not exclude such a scenario categorically. We may not understand how certain abstractions can be concretised, but this allows not the conclusion that certain concretisations must be impossible. Because we deal with abstractions through our limited faculties of reason, computation, sensibility etc., we must allow for the shortcomings of these faculties and the regular paradoxes which arise from them.

66. Protagoras will kindly remind us of his humana mensura: Man is the measure of knowledge. One should not speculate on what cannot be understood by human means. We all agree on that. But because we know not exactly the extent of human means and the capability of thought excited by the urge of investigation, we should not stop speculating and investigating for fear of losing the measure, as through the constant exercise of reason an idea which is now deemed metaphysical, unverifiable or simply wrong may lead to the truth eventually. Protagoras might not have considered the physical knowledge of this our time to be within human measure.

41

67. If also abstractions be, as I wrote above, a modality of matter, and if it be true that the complex derives from the simple as stated earlier, are abstractions such as numbers simple or complex? Being simple, how simple are they? Being complex, whence derive they? Let us suppose, for instance, that numbers are complex parts. Let us suppose numbers derive from something simpler, i.e. from the mere ability of computation, from intelligence, whereas intelligence, being more complex than non-intelligence, would necessarily derive from non-intelligence. In this scenario, it is the constant exercise of our computing ability that will give rise to numbers in our intelligence. If we suppose, on the other hand, that numbers are simple parts, it is numbers that will give rise to the ability of computation. In such a scenario, intelligence derives from numbers and is therefore more complex than numbers. We enquire nothing else as whether we should deal with numbers or with computation as the primitive element.

68. Whatever the answer to this question be, if we understand numbers as deriving from computation, we still cannot claim that computation exists only in human intelligence, because we know not the extent of intelligence outside our little world and our limited measure. We might still think of a scenario where a kind of computation, not necessarily “divine”, but anterior to ours, gave rise to the complex idea of numbers. This idea could then either have become resistant to its simple origin and given rise to further complex forms of computation and intelligence such as human, or a fortuitous power assembled it with other concepts to form intelligence. Numbers would then belong to the simplest parts of human thought, representing thought in its point of irreducibility. This is a possible scenario. And yet, if this power of computation gave rise to the idea of numbers, could it not count before? And if it could not count, could it not be counted by other intelligent powers?

42

69. Be that as it may, because existence cannot be caused, we cannot say that numbers or computation were caused by one or the other, created as if they had not existed before, but both will have always existed together. And, if in a certain place one appeared to be anterior to the other, this other one was present in its potentiality, because the ingredients that would form it existed everywhere. Both concrete and abstract existence have their distinct ingredients. However, these ingredients are transformations from the same original ingredients of existence as one phenomenon. So far, literature has thrived a great deal on science fiction. If nothing else in the above lines be of value, let Apollo the converser enjoy at least the creation of a new genre, metaphysical fiction, and let there be light. Amen.

| An Essay on Existence |

70. Hey, bloke, why are you sitting in the cold here like gaga? Gosh, you’ve just rubbernecked at me like a frightened sheep! What’s going on? I bet that girl cheated on you again. Is that it?

“I’ve just been thinking.”

About what?

“Forget it, mate, it’s crazy. You’ll just laugh at me.”

Come on! Let me sit down by your side, yeah, feels better now! Just let me know it all and I’ll help you, that’s what friends are there for.

43

71. “Well, I don’t know. I was thinking about the chicken.”

What?

“And the egg!”

You mean...

“...which came first.”

Ha, you make me laugh. Are you joking? You’re not telling me you’ve been sitting here for hours thinking bullocks. Why think about that? I don’t think you’ll know better at the end of the day.

“But I do!”

Oh right! Do tell!

72. “Now listen, listen quick before I lose my train of thought again. Excuse my French, but if you say the chicken came first, it’s rubbish because the chicken came from an egg, so the egg must have been there before, true? But of course, if you say the egg came first, it’s just the same shit again because the egg is there after some chicken laid it, true or false? True! Well then, that’s it, and I don’t like it. I like to sit down and think about a problem until I come up with a sort of solution for it. That’s the way I deal with things. The farthest I came so far is something like that. Listen: If the chicken came from the egg and the egg came from the chicken, then it’s pretty clear they belong together, like they cannot be without each other. They’re just the same thing and the one came together with the other. Yeah, no one is older than the other. There isn’t such a shit as chicken and egg, but the egg’s the chicken and the chicken’s the egg.”

44

Well, I don’t really want to get into that now, it’s quite cold here, outside. But yes, I think you got something of it. The chicken and the egg belong to each other as if they were the same thing, but only as if. You won’t mind me saying one or two things about that, will you? Not that I give a toss about that, I’m just thinking, just thinking about the biology of the whole. I mean, whoever came first, the egg and the chicken came from some odd ancestor in nature, isn’t it? And actually, the ancestor is the origin of them both, isn’t it? Which came first, then? Well, their common ancestor came first. It’s real weird, but it’s true!

73. “Hang on a second, hang on! You’re not trying to tell me that’s the answer to the problem, are you? That’s a load of rubbish and I tell you why. The question is not whether the egg and chicken have a common ancestor. Of course they have, everything has an ancestor, a cause of some sort. The question is still which came first, regardless of the ancestor.”

There’s no answer that won’t lead to the ancestor, mate. You’re looking for a cause, aren’t you? So the cause must be the ancestor, and the only question now is if the ancestor kind of came up with the egg or with the chicken first. Get it now?

“But then it’s still the same thing, you animal. There must have been a transition between the ancestor and the chicken and egg, so we still don’t know which came first in the transition. It could be the egg and it could be the chicken.”

45

74. You’re oversimplifying things a bit, aren’t you? As if the ancestor didn’t lay eggs himself, or herself I should say! So the problem is just sort of inherited, yeah. It starts with the bloody ancestor and we don’t know which came first, the egg of the ancestor or the ancestor itself.

“Wait! If you say the ancestor laid eggs, then the egg came first and only then the chicken, because the eggs that the ancestor laid were already eggs, while the ancestor himself was not yet a chicken. Cripes! It’s the egg that came first!”

Who’s saying that? That’s your assumption, and you may be talking through your ass again, of course you may! There’s no other way of putting it, because you are saying that the chicken and the ancestor are different as if the eggs were the same, but you don’t know anything about that. You don’t know if the eggs are the same, or if the chicken’s egg is the chicken’s egg and the ancestor’s egg is the ancestor’s egg. You’re taking two different things for the same thing. And again, even if the eggs are the same, who told you that the chicken is really something different from the ancestor? I’m not sure about that. I mean, not that I’m giving a shit to it, just saying, don’t know.

46